The health of the net-zero transition is in the eye of the beholder

In the era of ‘Schrödinger’s transition’

As with any complex and emotive issue, the net-zero transition attracts hyperbole from both its champions and its critics. Recent headlines paint a tumultuous picture: a Trump Administration launching “sweeping attacks on climate rules",1 a global climate order “teetering under assault"2 and an EU “struggl[ing] to balance green and growth goals."3 Concurrently, champions of the transition hail record low levelized costs of energy (LCOEs) for renewables and fastidiously report on the emergence of grids powered entirely by clean, intermittent energy. Such is the current reality of the net-zero transition; it is simultaneously described as both the doom of competitive economies and as an unstoppable economic force. As both impossible vanity and moral imperative. As both dead and alive. There can be no doubt, we have entered the era of Schrödinger’s transition.

The net-zero transition is facing headwinds; emerging anti-climate political ideologies, rising geopolitical competition, and increasing concerns over the intermittency of renewable energy represent real challenges. Yet, the narrative of net-zero’s demise is overstated. Global energy transition investment has doubled since 20204 and last year hit a record $2.1 trillion. At the forefront of the net-zero transition are clean energy technologies that enjoy strong fundamentals including favourable economics and access to increasingly sophisticated markets. While headwinds will slow momentum, they will not derail a transition that is increasingly driven by cost-competitiveness with models that assume only free market forces to drive technological uptake forecasting renewables to account for over 50% of global power generation by 2030 and 70% by 20505.

This piece explores why the net-zero transition may be slowed but will not be stopped. It outlines how renewable energy offers the fastest, most scalable solution to soaring global electricity demand, assesses renewables’ structural advantages over gas and nuclear power, and highlights Texas as a case study for clean energy growth despite political uncertainty. Further, it examines why banks still view the transition as a financial opportunity, and argues that emerging challenges facing the transition signal not failure but the inevitable growing pains of progress.

Leveraging renewables to meet demand growth in the ‘Age of Electricity’

Hotter summers, broad electrification, and the explosive growth of AI and data centres are propelling the global economy into an ‘Age of Electricity’. In the U.S. alone, rising electricity demand is set to add the equivalent of California’s current power consumption within three years6. Amid this boom, debates have intensified over which energy sources can scale fast enough to meet growing needs.

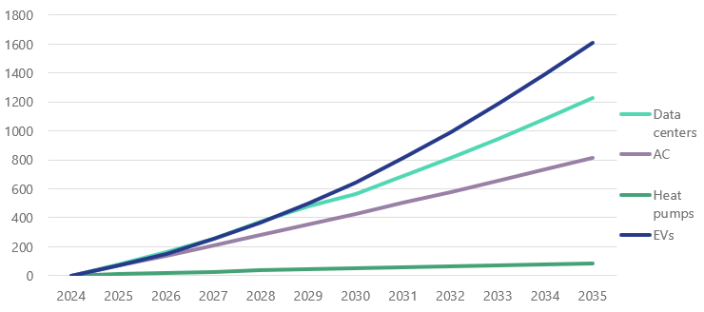

Figure 1: Select drivers of electricity demand growth, 2024-2035 (Terawatt-hours)7.

Natural gas, prized for its flexible, round-the-clock power, has become 2025’s vogue molecule. Yet gas will meet only a fraction of future demand. Constrained by slow development timelines and supply chain bottlenecks, even under optimistic assumptions gas-fired generation can provide just 16% of the 460 GWs needed by 20308. Furthermore, S&P Global projects that while the U.S. will need 60–100 GWs of additional gas capacity by 2040, it will require over 900 GWs of renewables and storage9 by the same year. Gas turbine manufacturers already face backlogs stretching beyond 202910, while in key US electricity markets renewables and storage boast far shorter build times; 26 months for wind and solar and 16 months for storage in comparison to 42 months for gas11.

Nuclear energy has also been heralded as a critical piece of the net-zero puzzle. It provides valuable baseload, low-carbon power, and efforts to extend plant lifetimes offer a cost-effective path to support grid capacity. However, a true nuclear renaissance remains uncertain. Nuclear faces long development timelines, economic challenges, and a rigorous regulatory environment. While it contributes 10% of global electricity today, scaling nuclear quickly and cost-effectively against other non-fossil technologies will be an immense challenge—especially given that commercial advanced reactors are unlikely before 2035.

The factors raised above underscore an undeniable and well-understood reality: renewables are the fastest option to meet new energy demand.

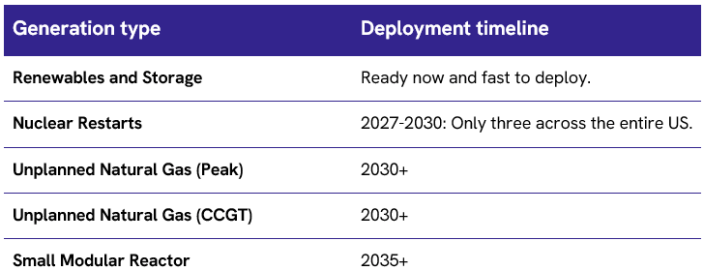

Figure 2: US energy asset deployment timelines by generation type12.

Energy asset deployment timelines and the ability to scale rapidly are pivotal considerations when assessing the defining force shaping 21st century geopolitical competition; the AI race. As the U.S. and China vie for AI supremacy - with massive military, economic, and political stakes - insufficient energy generating capacity will become the key hurdle to AI dominance. As Dr. Joshua Rhodes from the University of Texas at Austin emphasizes, "AI is not going to wait for 2030 to come. It is going to be won or lost in the next few years. And the things that you can build today are wind, solar, and storage13."

America’s net-zero paradox

Nowhere are the competing narratives of the net-zero transition more visible than in the United States. Pull on one thread and a political class emerges that is increasingly intent on weakening climate action, pull another and we find a booming clean energy economy that employs hundreds of thousands of workers and that in 2024 invested $338 billion in decarbonisation-related technologies.

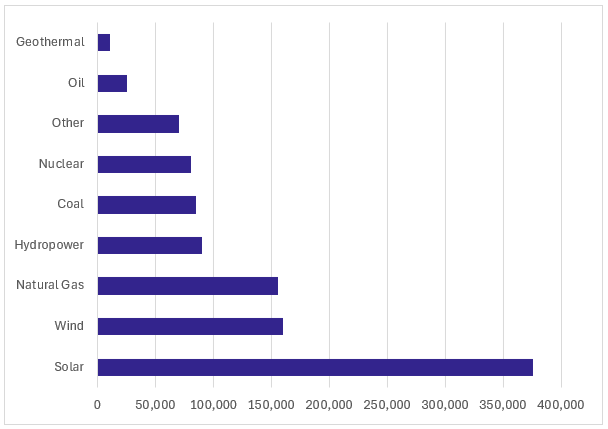

Figure 3: US jobs by power generating technology, 2023.14

Having been hailed as a landmark bill in 2022, President Biden’s cornerstone climate policy, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), now sits squarely in the crosshairs of a pro-fossil fuel and anti-climate Trump Administration. Yet even under worst-case scenarios that model a full and immediate repeal of IRA tax credits, projections still forecast the US adding 927 GWs of clean energy capacity over the next decade, only 17% below the base-case target of 1,118 GWs15. This would still represent a major jump from today’s 350 GWs renewable capacity. Further, in 2023, 95% of all new energy capacity waiting in U.S. grid connection queues was from renewable sources. Last year also saw renewables become the second-largest source of U.S. power generation, whilst zero-carbon sources accounted for 42% of total generation. The message is clear: while policy may slow the U.S.’ net-zero transition, it will not stop it.

Executive Orders, Congress, and the limits of political power

On his return to the Oval Office in 2025, President Trump issued Executive Orders aimed at dismantling the previous Biden Administration’s climate agenda. However, Executive Orders, while headline-grabbing, are often more symbolic than transformational. They instruct federal agencies but rarely enact immediate change and are vulnerable to both legal challenges and reversals by future administrations. With both houses of Congress under Republican control, the potential for deeper change still exists yet the IRA’s economic impact across rural Republican states poses hurdles to a full repeal.

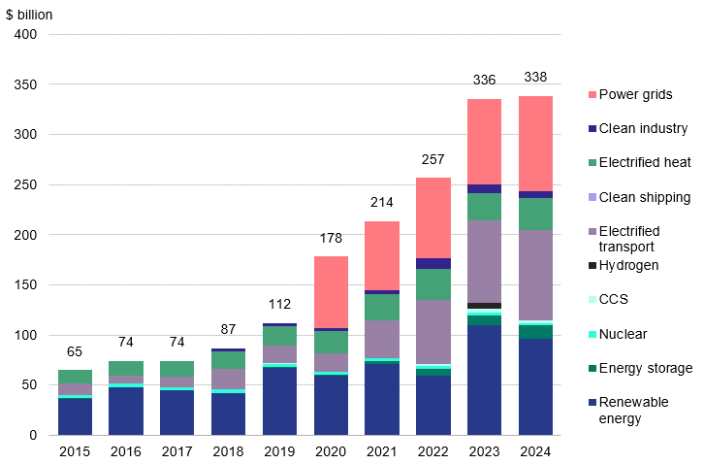

Figure 4: US energy transition investment, by sector.16

Moreover, whether Republicans approach the IRA with a scalpel or a sledgehammer, a focus on the key hurdle currently blocking the clean energy rollout – transmission - highlights why a rollback of clean energy related tax credits should not be viewed as the death knell of the United States clean energy industry.

Looking beyond subsidies: there is no transition without transmission

The key to long-term decarbonisation remains the availability of cheap, unsubsidised clean energy. The IRA’s tax credits were designed to spur the production of cheap clean energy however this ignored the reality that solar and wind were already incredibly cost-competitive. Rather than achieving cost parity, today the challenge is getting cheap, clean electricity to where it is most valuable. Renewable assets often cluster geographically, producing power simultaneously and depressing the marginal value of their produced energy. Without sufficient transmission to move power across regions, the financial returns of renewable projects erode as their grid penetration levels rise. The future profitability of renewables therefore now hinges less on subsidies and more on transmission and interconnection reform. As subsidies sunset, attention must shift to building out transmission capacity, easing permitting, and reforming grid interconnections. Here, bipartisan dealmaking in Congress remains possible.

As the saying goes, you campaign in poetry, yet you govern in prose. Whilst campaigning is often reliant on idealism and emotional appeal, governing requires straightforwardness, clarity and practicality. These dynamics will ring true in Congress’ approach toward climate reform. Legislative realities - particularly the Senate filibuster - limit any one party’s ability to reshape the policy landscape unilaterally. While Republicans can pursue certain budgetary changes via reconciliation, altering environmental and energy statutes will require bipartisan cooperation. Republican priorities such as loosening permitting laws will require 60 votes to overcome the Senate’s filibuster, limiting their ability to favour fossil fuels without a quid pro quo agreement with Democrat Senators to benefit renewables and electric transmission. Away from Capitol Hill, a look to the Texan economy evidences the unlikely coalitions that can form around the net-zero transition.

Texas: where economics can trump politics

Over a 12-month period spanning 2023 and 2024, Texas added more solar capacity per capita than any U.S. state or any country worldwide17. Looser regulation, vast land availability, and rural revenue opportunities have made renewables extremely attractive - even in a state synonymous with oil and gas. Today, conservative stronghold Texas outpaces even California in terms of rolling power generation from all clean sources. This dynamic points to a widely observed phenomenon, "economics often triumphs over politics and ideology18." The broader investment data from 2023 mirrored this trend, with global investment in low-carbon energy overtaking fossil fuels for the first time. The year’s 1.11:1 investment ratio meant that for every $1 invested into fossil fuels, $1.11 was invested into clean energy assets19. While still far from the 4:1 ratio needed to meet 1.5°C targets, the takeaway is unmistakable: economics increasingly shapes politics.

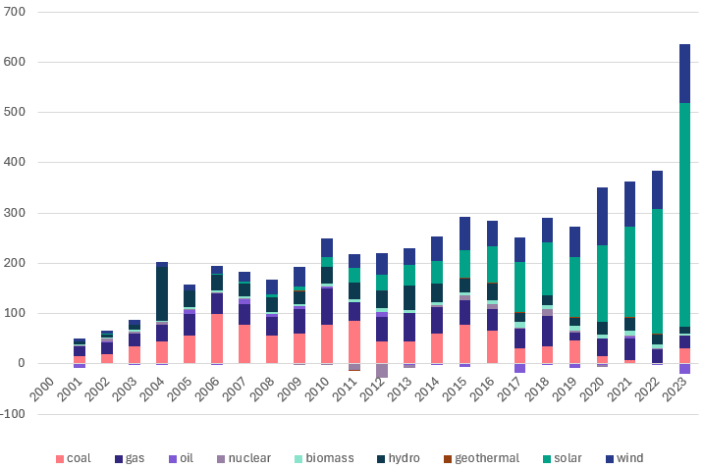

Figure 5: US electric generating capacity (GW) year-on-year change, by fuel type.20

Wall Street adjusts, but its financing endures

Away from the real economy, Wall Street’s reaction to the Trump Administration’s political pressure has been symbolic rather than structural. Major U.S. banks have withdrawn from the UN’s Net-Zero Banking Alliance under the new Trump administration, yet they all reaffirmed their net-zero and sustainable finance goals. At their core banks exist to make money. Clean energy and net-zero technologies already generate $4 trillion21 in annual revenues and this a growing opportunity banks are unlikely to abandon. To this point, bank financing ratios are also gradually shifting, with fossil fuel lending falling and low-carbon lending rising. In 2023, U.S. banks facilitated 89 cents of low-carbon financing for every $1 in fossil fuels - up from 78 cents in 202122. It is clear then that despite headline-grabbing exits from voluntary alliances, the financial incentives underpinning the transition remain intact and attractive.

Emission Impossible? Entering the hard part of the journey

Much of the hyperbole around the net-zero transition has meant that real challenges are accompanied by exaggerated ones. Negative prices, duck curves, and grid reform have long been forecast and the solutions to these issues are well-researched and articulated. Rather than existential threats, their arrival signals how rapidly the transition has scaled and progressed. However, it is undeniable that focus must now shift to addressing tougher problems: boosting storage, flexibility, and transmission, scaling clean energy in developing markets, and decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors.

Progress also demands embracing a cognitive dissonance: private finance will only pay for the net-zero transition if it delivers worthwhile returns. A successful transition must be a profitable one or it will not materialize. As Albert Cheung, BNEF’s Deputy CEO, succinctly summarised, “there is no world in which public or concessional capital alone can solve the climate mitigation challenge.” Investment in the net-zero transition has doubled since 2020, yet investment levels are welded to a growth curve that is consistently below the level it needs to be on. Addressing this paradox requires reflection that the net-zero transition is becoming increasingly two-tiered. Renewables, storage and EVs are technologies that are well-placed to continue scaling whether they have concerted policy backing or not. However, the emerging second tier of technologies that will address hard-to-abate sectors - CCS, hydrogen, and low-carbon heat - will require government backing and support. For these technologies to successfully scale, consistent policy will be the cornerstone required for unlocking capital. It is also fundamentally in the best interests of governments to create this investing environment; ignoring the science and economics of climate change does not mean a nation will avoid the climate-related physical disasters increasingly being seen.

Momentum through uncertainty: the net-zero transition endures

The net-zero transition is not a speculative ambition - it is a structural economic shift underpinned by powerful market forces, sophisticated technologies, and maturing end markets. Policy, macroeconomic environments, and technological innovation will continue to shape the speed of this transition, but its fundamental direction remains unchanged. Investment trends are already proving more resilient than political cycles and where financial and economic opportunities exist, momentum will follow. Moving forward, success will hinge on the leadership of policymakers, the foresight of investors, and the ability of market participants to propel the transition through its challenging yet pivotal next phase. The question now is not whether the net-zero transition will happen, but how effectively it can be scaled to meet the needs of an increasingly electrified, digital, and climate-conscious global economy.

Written by Louis Bromfield - Lead Sustainability Manager, Foresight Capital Management

Sign up here to receive our monthly and quarterly commentaries in your inbox.

1 Natter, A. and Dlouhy, J.A. (2025) Trump Mounts Sweeping Attack on Pollution and Climate Rules, Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

2 Rathi, A., Krukowska, E. and Cang, A. (2025) The Global Climate Order Teeters Under Second Assault by Trump, Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

3 Mundy, S. (2025) EU struggles to balance its green and growth goals, Financial Times.

4 Cheung, A. (2025). Energy Transition Investment Trends 2025. BloombergNEF.

5 White, T. (2025). Sustainable Finance after US banks quit net zero group: REACT. BloombergNEF.

6 Ibid

7 Various Authors (2025), New Energy Outlook 2025, BloombergNEF.

8 Casey, S, & Malik, N. (2025). Top US utility says gas can meet only a fraction of power demand. Bloomberg UK.

9 S&P Global Commodity Insights. (2025). US National Power Demand Study - Electricity Demand Returns To Growth

10 Arun, A. (2025). The Natural Gas Turbine Crisis. Heatmap News.

11 Electric Reliability of Texas Demand and Reserve Report (2024)

12 NextEra Energy Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2024 Conference Call. 4Q 2024 Slides vFinal.pdf.

13 Drane, A. and Hao, C. (2025). Fact check: Trump officials say wind is bad for Texas power bills. [online] Houston Chronicle.

14 Sustainable Energy in America factbook: 2025 edition (2025) BloombergNEF.

15 Various Authors (2024). The Energy Transition Enters the Age of Trump II. [online] BloombergNEF.

16 Various Authors (2025). Energy Transition Investment Trends 2025: Countries Annex. BloombergNEF.

17 Burn-Murdoch, J. (2024). How red Texas became a model for green energy. Financial Times.

18 Ibid.

19 Various Authors (2025) Third Annual Energy Supply Investment and Banking Ratios: comparing low-carbon and fossil-fuel activity, 2021-2023, BloombergNEF.

20 United States Power Capacity Overview. BloombergNEF.

21 White, T. (2025) Sustainable Finance After US Banks Quit Net Zero Group: React, BloombergNEF.

22 Ibid.