Beyond the numbers: What selling Linde really means for our climate engagement

Exiting Linde

This quarter we made the decision to sell the WHEB Strategy’s position in Linde. Linde produces industrial gases which are used in a variety of applications that have a positive impact including healthcare, water treatment, as well as in improving energy efficiency in buildings and manufacturing processes.

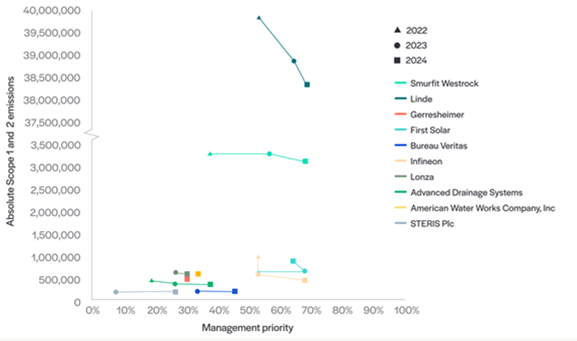

However, for the period Linde was in the strategy it also represented a very significant proportion (25 -60%)1 of our financed emissions (Figure 1). The company was therefore a priority for engagement to encourage a comprehensive approach to reducing these emissions.

In selling Linde, the portfolio’s emissions have fallen sharply. But Linde’s real-world emissions remain unchanged. So, where does this leave us in the context of our climate commitments and stewardship responsibilities? Does divestment undermine engagement goals? And can it still drive change?

Figure 1: Changes in Scope 1-2 emissions from the Funds’ top emitters2 (2022-2024)

A ‘fundamentals first’ decision

Financial fundamentals ultimately drove the decision to sell.

We were concerned about Linde’s ability to expand margins and its loss of share price momentum, though we continue to believe its core business delivers meaningful impact. Industrial gases will play an important role in healthcare as well as in decarbonising many downstream industries, especially in manufacturing.

The reporting paradox

Still, the production of industrial gases remains highly energy-intensive due to a reliance on fossil fuels. Given Linde’s outsized contribution to the Fund’s carbon profile, selling our position means that the Fund’s financed emissions at the end of Q3 2025 are now 38% lower than they were at the end of Q23.

This highlights a familiar tension between what the data shows and what happens in the real world. Financed portfolio emissions have fallen, but without a corresponding real-world impact. There’s a risk therefore that investors and their clients can end up celebrating an optical illusion.

This paradox is not unique to WHEB. It’s a reality faced by most equity investors where sell decisions made for fundamental reasons can have unintended, but superficially positive, reporting outcomes.

WHEB’s journey engaging Linde

Given its position as the portfolio’s largest emitter, Linde has been a key focus of WHEB’s climate engagement since we formalised net-zero carbon (NZC) commitments in 2019. Linde has since made meaningful progress against objectives set by WHEB and other investors to strengthen its climate strategy (shown by ‘Management priority’ in Figure 1). These included the creation of a Board-level sustainability committee, adoption of a Science Based Target initiative (SBTi)-validated NZC target, and a faster carbon reduction timetable.

More recently, we attended Linde’s 2025 AGM and had a constructive discussion with the board about accelerating the decarbonisation of its fossil-fuel-based air separation units (ASUs) and expanding renewable power purchase agreements (PPAs).

From an engagement perspective, selling our position in Linde felt premature. Progress was visible, but there was still much more to achieve.

Divestment: its role and limits

In stewardship, divestment is usually a last-resort escalation tool. Evidence suggests divestment often shifts ownership to less responsible investors, limiting its influence.4

But selling Linde was not an escalation, it was a decision based on fundamentals. Given the multi-year engagement and ongoing progress on exiting our investment, we wrote to Linde, explaining our position and thanking the company for over a decade of constructive dialogue, highlighting both achievements and areas for further action, including:

- Electrifying the company’s remaining fossil-fuel ASUs;

- Further expanding renewable PPAs;

- Developing blue and green hydrogen markets; and,

- Aligning public policy activities with climate goals.

Although this sale ends our direct engagement, Linde remains in our investment universe. We continue to support collaborative initiatives like the IIGCC Net Zero Engagement Initiative and ShareAction’s Chemicals Decarbonisation Working Group.

It’s worth noting that we still believe divestment, when used thoughtfully, has its place in engagement. Our exit from Daikin, following its involvement in white phosphorus weapons, helped reinforce broader investor pressure that ultimately led the company to end this activity.

Wait - but what about the reporting paradox?

Linde accounted for 33% of financed emissions and 68% of absolute company-level emissions at the time of sale5. Its removal materially improves our reported performance year-on-year but, without any corresponding reduction in atmospheric emissions.

This illustrates a core challenge in climate reporting. Our NZC reporting attempts to overcome this by using both financed emissions to guide engagement6 and absolute company emissions to track progress7. Together, they ensure our influence is targeted where it can drive meaningful change.

Looking ahead: commitments and engagement

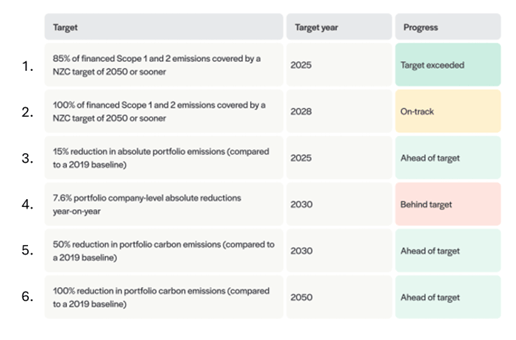

Despite selling Linde, we continue to exceed NZC Target 1 and remain on track for Target 2 (Figure 2):

- 94% of financed emissions are now covered by a net zero commitment

- 91% by SBTi-validated carbon reduction target

Figure 2: WHEB Sustainable Impact Fund net-zero carbon (NZC) targets and progress as of June 2025.

The reshaped top 10 emitters now account for 90% of financed emissions. Of these, only American Water Works, which replaces Linde in the top 10 emitters, lacks an SBTi-validated NZC target. This will likely be an engagement priority going forward as we focus on real-world decarbonisation.

Conclusion

Effective climate stewardship is about more than presenting numbers that tell the story we might want to hear. It’s about driving real, lasting decarbonisation that reduces risk and makes our investments more resilient. It also means being honest in how we report progress and clear about how divestment fits alongside engagement as part of a thoughtful, principles-based approach.

Selling Linde doesn’t mark the end of our climate engagement journey. Rather, it opens the door to new ones as we renew our focus on the top emitters in the portfolio to help move the needle on real-world emissions.

1 These figures are based on Scope 1 and 2 emissions allocated to WHEB in proportion to our ownership of Linde. Because Linde is a very large and carbon-intensive company, even a relatively small investment meant it accounted for a big share of the portfolio’s financed emissions. A small change in portfolio weighting can therefore lead to a large swing in the percentage of financed emissions attributed to a single company. This is why Linde’s contribution ranged from 25% to 60% over time.

2 Top emitters defined as the ten portfolio companies with the highest financed Scope 1 and Scope 2 (market based) emissions. They are ranked in the legend in order of largest to smallest financed emissions.

3 Source: Net Purpose

4 https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hart/files/exit_vs_voice_dec2022.pdf

5 Source: Net Purpose

6 Financed emissions: A company’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions, allocated to investors based on ownership share. This highlights which holdings most affect the portfolio’s carbon footprint and where engagement can be most effective.

7 Absolute emissions: The total Scope 1 and 2 emissions a company produces, regardless of ownership. This shows the company’s real-world climate impact and progress on decarbonisation.